I recently visited with a middle school leader who talked about the school's new plan for discipline. It was a loving and supportive environment from staff to student, but students frequently responded inappropriately and unkindly to one another and staff. She said the issue was highlighted by a statement from one student, "I know they [teachers] love me even when I'm rude to them." It seemed students were getting the message that they were cared for but did not feel compelled to demonstrate that care back.

She told me they were moving towards zero-tolerance around teasing and back-talk to behavior redirection. That is, teasing would lead to an automatic detention and back-talk to an automatic out-of-class referral for the remainder of the period. In setting a tough line, the school hoped to reign in this behavior.

Thinking back to my days in the classroom, especially the early years, this didn't seem crazy. I remember how many punches I took from kids misdirecting their anger over what seemed to be simple and reasonable behavior redirections. Their reactivity seemed so extreme that it needed to stop, and I didn't always feel that I had the tools to make that happen. Zero-tolerance seemed like a straight-forward way of curtailing these behaviors that caused so much disruption.

The issue with zero-tolerance, however, is that it addresses the behavior as the problem rather than the symptom. It suggests aggressive reactivity is a choice. However, for the students of this school, and those I formerly taught, many were raised with insecure attachments in households that were traumatic. In such cases, students are not choosing their responses. They react protectively to what they see as a threat. That the "threat" might be a simple request to hold a conversation until after directions are given does not change the fact that the child perceived it as dangerous.

In The Invisible Classroom, Kirke Olson does an incredible job of using neuroscience to explain student reactivity, and he provides best practices to work with students who exhibit antisocial behavior. He explains that all nervous systems are continuously — once every quarter of a second — scanning for threats in the environment. When students aren't safe in childhood, they have weaker connections between the prefrontal cortex, or rational brain, and limbic system, or threat-detection center. Furthermore, when students perceive an environment as threatening, their brains are trained to look for confirming experiences, and sometimes find them in innocuous exchanges. As such, they respond to nonthreatening stimuli as if it they are literally life-threatening. Their bodies go into a state of sympathetic arousal much quicker than those with stable systems. A high state of sympathetic activation takes their prefrontal cortex off-line. In this "fight or flight" mode, they are incapable of making rational decisions and unavailable for learning.

In this context, stricter discipline means creating a more threatening environment for those who struggle with emotional regulation. Punishing reactions to redirection only serves to confirm that school is, indeed, an unsafe place for that student. The root of the problem is still unaddressed — students do not trust their environment, and this lack of trust exacerbates defensiveness.

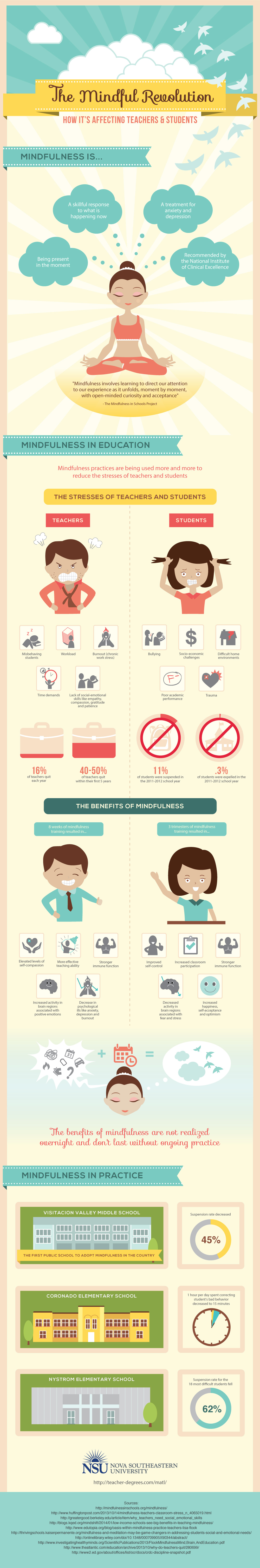

An alternative approach, according to Olson, is a trifecta of preventative measures that will build culture by creating positive behaviors for students. Creating an environment where students' nervous systems are mostly in the ventral vegal parasympathetic, or resting state, is the only way to ensure learning will occur. Olson suggests teachers must nurture strong, genuine relationships with their students. As relational beings, we are hardwired to seek and depend on relationships to learn about the world. Additionally, taking a strength-based approach to students allows them to feel comfortable in a school environment. Finally, students should be trained in mindfulness so that they can learn how to create space to respond rather than react.

In reflecting on the comment, "I know they [teachers] love me even when I'm rude to them," the love at this school appears to be transmitted to students. However, this student didn't always have the tools to respond appropriately to staff. Consistently working with mindfulness can help that student find space when she is feeling reactive and provide tools to use in those moments. She needs time the school day to practice using them in a safe space. Cultivating heartfulness, a practice of mindfulness that creates feelings of compassion, may help that student feel empathy for and connection to others. Building and sustaining such states will help her remain connected to her prefrontal cortex and less likely to react with volatility.

It is not unreasonable to set high expectations around the way our students treat others; however, we must cultivate a culture of compassion amongst them. We cannot simply tell them to change their behavior; we must teach them how to change their behavior.

For another in-depth look into this issue, check out Katherine Lewis' "What if Everything You Knew About Disciplining Kids Was Wrong."